It’s 2063; Will Africa still wait?

“Predictions aren’t the means to judge a futurist. The impact they make on the world is.”—Aaron Saenz

You might ask, “Is it possible to predict the future?”

Of course it is. People accurately predict the future… at least some of the time. The problem is, you can never guarantee that a prediction will be accurate. Even if you could see the future, a prediction about the future might not be accurate, because acting on that future information could change the information by the time you reach that future.

“The Best Way to Predict the Future Is To Create It”

That phrase, when searched in quotes on Google, returned 435,000 results. To me, this means people believe it to be true. Physics tells us that we all have a part in the future, through cause and effect. But can we change the future, or are we part of the chain reaction of cause and effect that never ends, with no bearing on the outcome, because we have no true free will? I’ll leave that to the philosophers and to the scientists.

Before sprint KNUST; I had used Natural Language Processing to analyze the sentiments of people on Twitter on CITI FM’s Bernard Avle speech at an event on November 28, 2018. It was an event in Ghana.

The conversation was under the theme “Rethinking the National Conversation”.

The official hashtag for the event was #Avlespeaks. After collecting over 5,000 tweets containing this hashtag at the time of the event via the Twitter API, I first preprocessed and cleaned the textual data in a Python notebook.

I then used Google’s langdetect library to filter out non-English tweets and dropped all the retweets from the NLP analysis so that there was no doubling-up. After these steps, I was left with 2,780 unique tweets. Next, I used the Google Cloud Natural Language API to get the sentiment for each tweet.

Finally, I used the gensim library’s Word2Vec model to get word-embeddings vectors for each word in the entire corpus of tweets in relation to the word “Avlespeaks”. Word2Vec is used to compute the similarity between words from a large corpus.

Once I had vectors for each word, I then used the scikitlearn library to perform principal component analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction and to plot the most similar words (nearest neighbors) to “Avlespeaks”.

The sentiment for each tweet was calculated using Google’s Cloud NLP API. A bar graph indicated the average sentiment of tweets per day, with -1 being very negative sentiment and +1 being very positive sentiment.

At the end the results showed that Avlespeaks started out with a relatively low average sentiment that gradually increased as the week went on. There was a peak of 0.53 on Wednesday 29th November, which was the day after the conversation— people were clearly happy about this!

A night later, I had texted Geroge Sarpong on a very controversial conversation. It was about the zeal in young people to write motivational books in recent times. Isaac Boakye will say, you need discipline in this discourse.

And I made a suggestion about a platform that will enable these young people to write digital books with text to speech features using NLP and computer vision. This will make it easier for interested readers to subscribe and read these books easily.

Conversations about Artificial Intelligence adoption seems to harbor around few researchers and enthusiast in Africa. The map below distinguishes the pivotal roles being played by both developed and emerging countries across the globe of this new oil.

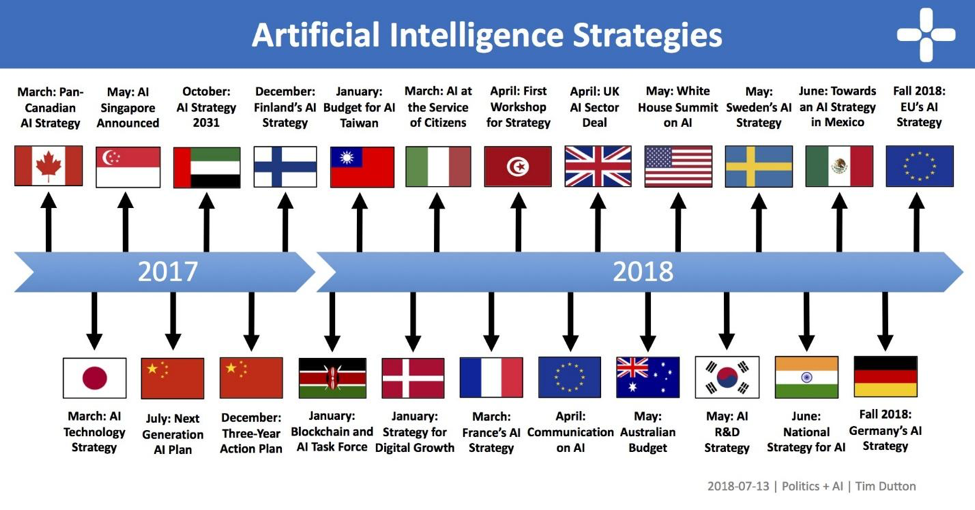

Several nations have already drawn their plans and reports on Artificial Intelligence (AI), Canada first published its AI plan in March 2017. China later published its detailed AI plan, A Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan in July 2017 where they outlined initiatives and goals to become equal to other AI powerhouses by 2020, lead the world in some aspects of AI by 2025 and entirely dominate as the primary center for AI innovation by 2030. Other nations and bodies have reacted by drawing theirs since then, among them are France, UAE, South Korea, India, EU, Germany, Mexico, Australia and USA. In just 17 months, at least 23 nations and bodies have published some form of plan for AI development. Kenya and Tunisia are the only nations from Africa among them with any attempt towards developing an AI plan.

The importance of such AI plans lies in the power that AI currently has and would have on the future. AI would add $15.7 trillion to the Global Economy by 2030 and potentially increase labor productivity by up to 40% by 2035. AI also has the potential to double the economy of a nation like the USA (GDP: 18.57 trillion) in just 20 years.

This has led to the AI Race among nations.

My senior Colleague, Darlington Ahiale Akogo of Mino Health Lab made this known at AI Expo Africa 2018 in Cape Town, South Africa.

It’s important for Africa to start planning now towards an AI future. Developing Economies like ours are the most threatened by such developments when not addressed properly. For example, a report recently showed automation technologies could perform 65% of the jobs in Nigeria, 67% of the jobs in South Africa and 85% of the jobs in Ethiopia by 2030, compared to 35% and 47% of the UK and USA, respectively. Even if we fail to locally develop AI systems, just like Africa consumes software and services from America like Facebook or Google, institutions in Africa would end up as consumers for foreign AI systems and we would all just be data points. In the long run, when the world starts approaching the Post-Work era due to high levels of automation and many countries begin implementing systems such as Universal Basic Income (UBI) by heavily taxing AI and Automation companies, we would likely be left even poorer and incapable of implementing such social safety nets since there aren’t enough local AI companies to tax.

Assefa is a computer scientist, a futurist, and a utopian—but a pragmatic one at that. He is founder and chief executive of iCog, the first artificial intelligence (AI) lab in Ethiopia, and a stone’s throw from the home of Lucy.

iCog Labs launched in 2013 with $50,000 and just four programmers. Today, halfway up an unassuming tower block, dozens of software developers type in silence. Their desks are cluttered with electronic components and dismembered robot body parts, from a soccer-playing bot called Abebe to a miniature robo-Einstein. An earlier prototype of Sophia, a widely recognized humanoid robot developed by Hong Kong-based company Hanson Robotics (she appeared with late-night talk show host Jimmy Fallon last year) is here too. Arguably the world’s most famous robot of her kind, Sophia’s software was partly developed in Ethiopia’s capital.

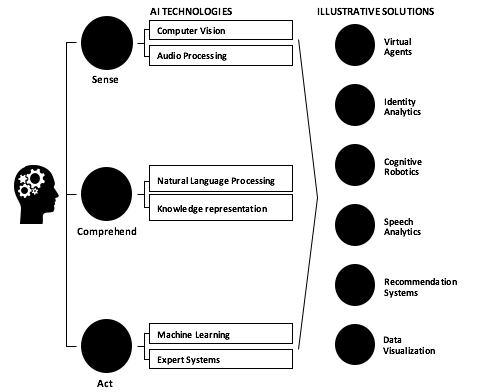

Artificial intelligence (AI) refers to systems that display intelligent behavior by analyzing their environment and taking actions – with some degree of autonomy – to achieve specific goals. AI-based systems can be purely software-based, acting in the virtual world (e.g. voice assistants, image analysis software, search engines, speech and face recognition systems) or AI can be embedded in hardware devices (e.g. advanced robots, autonomous cars, drones or Internet of Things applications). We are using AI on a daily basis, e.g. to translate languages, generate subtitles in videos or to block email spam. Many AI technologies require data to improve their performance. Once they perform well, they can help improve and automate decision making in the same domain. For example, an AI system will be trained and then used to spot cyberattacks on the basis of data from the concerned network or system.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is already part of our lives – it is not science fiction. From using a virtual personal assistant to organize our working day, to travelling in a self-driving vehicle, to our phones suggesting songs or restaurants that we might like, AI is a reality. Beyond making our lives easier, AI is helping us to solve some of the world’s biggest challenges: from treating chronic diseases or reducing fatality rates in traffic accidents1 to fighting climate change or anticipating cybersecurity threats.

There are some of the many examples of what we know AI can do across all sectors, from energy to education, from financial services to construction. Countless more examples that cannot be imagined today will emerge over the next decade. Like the steam engine or electricity in the past, AI is transforming our world, our society and our industry. Growth in computing power, availability of data and progress in algorithms have turned AI into one of the most strategic technologies of the 21st century. The stakes could not be higher. The way we approach AI will define the world we live in. Amid fierce global competition, a solid African framework is needed.

“African companies that invest in Africa have clear confidence in her long-term growth potential; they are at the cutting edge of their industries and, moreover, are capitalizing on their African context to generate higher returns. The highlights, lessons and checklist solutions in this report signpost what it will take for other companies and policymakers to promote an ‘invest with impact’ approach in Africa.”— Akinwumi A. Adesina President African Development Bank Group.

The world around us is changing at a furious pace. It’s left many established businesses shaken, with executives questioning their organisations’ longevity. To participate in a digital future, business transformation is critical and increasingly urgent. A strategic approach is essential. To help businesses chart the way forward, Accenture has partnered with the Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) of South Africa to provide insight into digital technologies and the future of business in 2017.

In fact, most executives agree that AI will revolutionise the way they gain information from and interact with customers. In South Africa, some 78% of South African executives say they need to boost their organization’s competitiveness by innovating through investments in AI technologies, notably embedded AI solutions and computer vision. But the reality, though, is that only about a third of these organisations are planning significant AI investments over the next three years.

Africa’s current population of around 1.2 billion is projected to double over the next 30 years, making Africa an exception in a world of slowing population growth. Moreover, it will soon be the fastest-urbanizing region in the world. Africa already has as many cities with more than one million inhabitants as North America does, and more than 80 percent of its population growth over the next two decades will occur in cities. The income per capita of Africa’s cities is more than double the continental average, making them attractive markets for many businesses.

McKinsey’s database of large companies with business in Africa reveals surprising figures: 400 companies earning revenues of $1 billion or more and nearly 700 companies with revenue greater than $500 million. These companies are increasingly regional or pan-African. They have grown faster than their peers in the rest of the world in local currency terms, and they are also more profitable than their global peers in most sectors. Between them, they boasted $1.4 trillion in revenues in 2015. Around two-fifths of them are publicly listed, and the remainder are privately held. Just over half are owned by Africa-based private shareholders, while 27 percent are foreign-based multinationals and 17 percent are state-owned enterprises.

To compete in Africa, companies need to pick the right geographic and industry trends to ride. Those with exposure to big or fast-growing cities, such as Luanda, for example, have better odds of outperforming.

Africa is home to a consumer class whose spending outstrips India’s, and it will soon have double the number of smartphone connections than North America. Yet poverty remains widespread, as do infrastructure gaps, fragmented markets, and regulatory complexity. By recasting challenges as a spur for innovation, and unmet market demand as room for growth, business leaders can help their companies, and the continent, to thrive.

African countries are one of those spearheading the UN Sustainable Development Goals and the unfortunate thing there has been no clear cut vision on how we it intends to achieve these goals.

One of the critical problems in Africa is its bleeding unemployment among its few trained human resources. Governments are struggling to provide jobs to these young people and it’s adversely affecting productivity in almost every sector.

Artificial Intelligence roadmap by the continent will not answer all of its problems but will speed the rate of development in the region.

The “AI for Social Good” was one of the workshops at NEURIPS in Montreal in 2018. It was to focus on social problems for which artificial intelligence has the potential to offer meaningful solutions. The problems we chose to focus on are inspired by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a set of seventeen objectives that must be addressed in order to bring the world to a more equitable, prosperous, and sustainable path. In particular, we will focus on the following areas: health, education, protecting democracy, urban planning, and assistive technology for people with disabilities, agriculture, environmental sustainability, economic inequality, social welfare and justice. Each of these themes present opportunities for AI to meaningfully impact society by reducing human suffering and improving our democracies.

The AI for Social Good workshop divides the in-focus problem areas into thematic blocks of talks, panels, breakout planning sessions, and posters. Particular emphasis is given to celebrating recent achievements in AI solutions, and fostering collaborations for the next generation of solutions for social good.

First, the workshop featured a series of invited talks and panels on agriculture and environmental protection, education, health and assistive technologies, urban planning and social services. Secondly, it brought together ML researchers, leaders of social impact, people who see the needs in the field as well as philanthropists in a forum to present and discuss interesting research ideas and applications with the potential to address social issues. Indeed, the rapidly expanding field of AI has the potential to transform many aspects of our lives. However, two main problems arise when attempting to tackle social issues. There are few venues in which to share successes and failures in research at the intersection of AI and social problems, an absence this workshop is designed to address by showcasing these marginalized but impactful works of research. Also, it is difficult to find and evaluate problems to address for researchers with an interest on having a social impact. We hope this will inspire the creation of new tools by the community to tackle these important problems. Also, this workshop promotes the sharing of information about datasets and potential projects which could interest machine learning researchers who want to apply their skills for social good.

WAY FORWARD

Google announced the setup of AI residency program at the company’s lab opened in Accra, Ghana.

Among other things are few initiatives by research institutions and universities to embark on AI works in their own small ways.

Key takeaways include:

- Supporting the national AI R&D ecosystem. Africa need to strengthen its human resource with unique R&D ecosystem that taps into the limitless bounds of African ingenuity. We need to discuss our free market approach to scientific discovery that harnesses the combined strengths of government, industry, and academia and examined new ways to form stronger public-private partnerships to accelerate AI R&D.

- Developing the African workforce to take full advantage of the benefits of AI. AI and related technologies are creating new types of jobs and demand for new technical skills across industries. At the same time, many existing occupations will significantly change or become obsolete. We need to discuss efforts to prepare Africa for the jobs of the future, from a renewed focus on STEM education throughout childhood and beyond, to technical apprenticeships, reskilling, and lifelong learning programs to better match Africa’s skills with the needs of industry.

- Removing barriers to AI innovation in the member states. Overly burdensome regulations do not stop innovation – they just move it overseas. We need to address the importance of maintaining African leadership in AI and emerging technologies, and promoting AI R&D collaboration among Africa’s allies. We need to also raise the need to promote awareness of AI so that the public can better understand how these technologies work and how they can benefit our daily lives.

- Enabling high-impact, sector-specific applications of AI. We need to be organized into industry-specific sessions to share the novel ways industry leaders are using AI technologies to empower the African workforce, grow their businesses, and better serve their customers.

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS.

Civilization reminds me of the trade that took place in the region about 400 years ago.

We suffered for many reasons and the memories still lingers.

Our proactiveness to things will help to save our people and the continent from mass destruction.

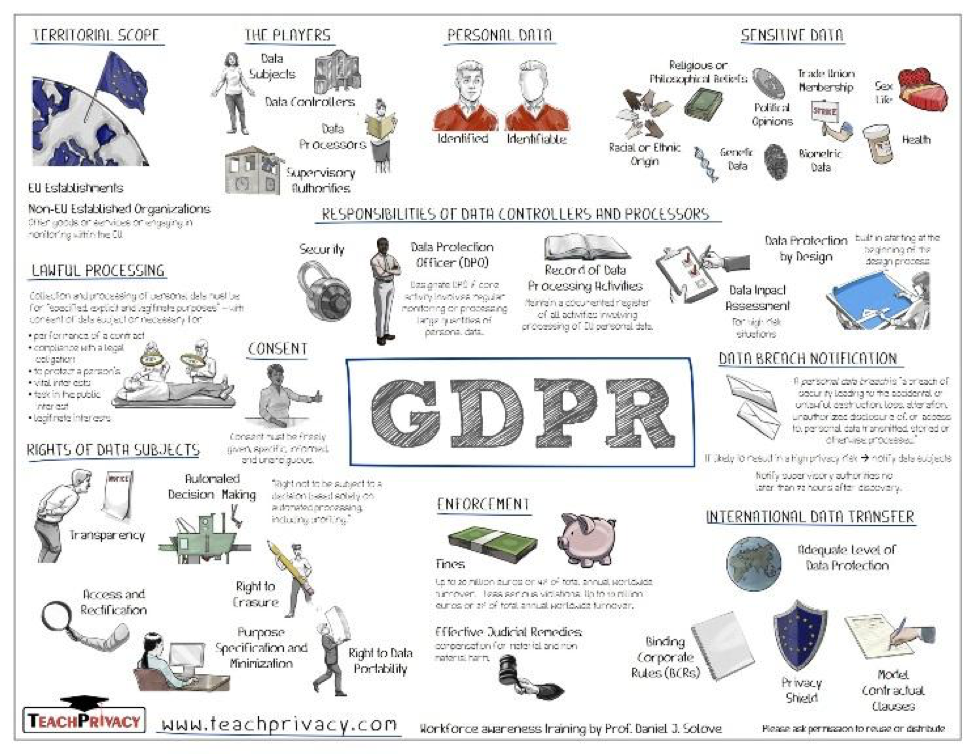

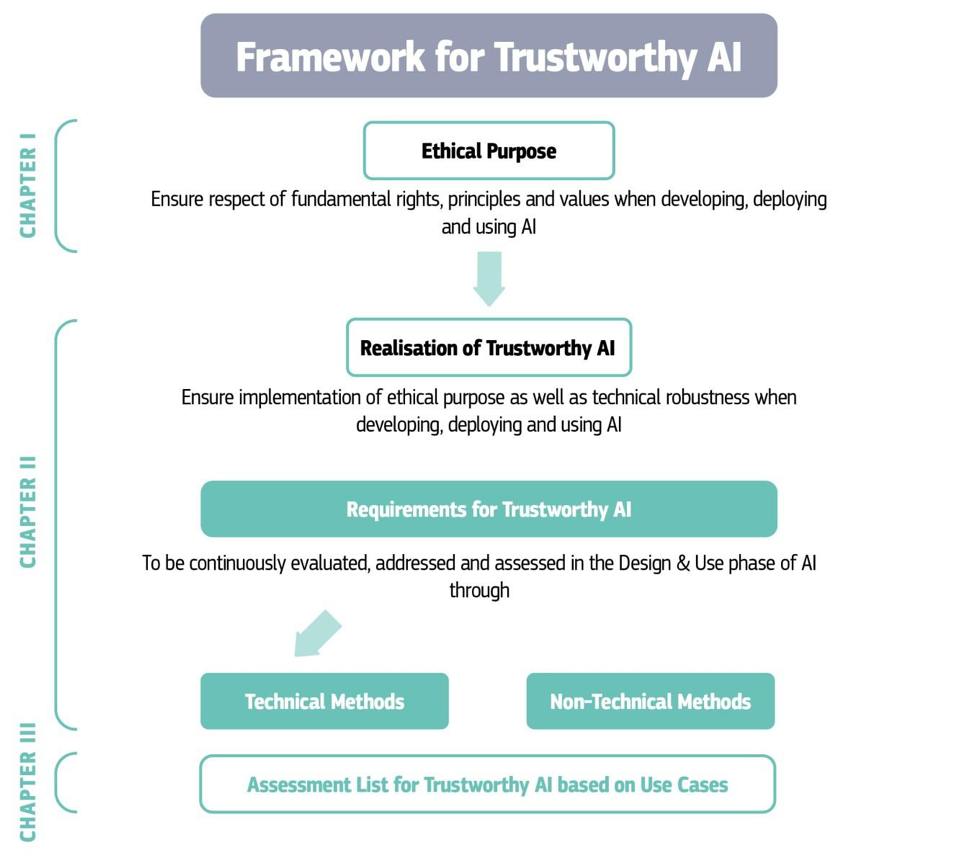

The European Union has released its working document which constitutes a draft of the AI Ethics Guidelines produced by the European Commission’s High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence (AI HLEG), of which a final version is due in March 2019.

AI’s benefits outweigh its risks, we must ensure to follow the road that maximizes the benefits of AI while minimizing its risks. To ensure that we stay on the right track, a human-centric approach to AI is needed, forcing us to keep in mind that the development and use of AI should not be seen as a means in itself, but as having the goal to increase human well-being. Trustworthy AI will be our north star, since human beings will only be able to confidently and fully reap the benefits of AI if they can trust the technology.

The Guidelines are addressed to all relevant stakeholders developing, deploying or using AI, encompassing companies, organizations, researchers, public services, institutions, individuals or other entities. In the final version of these Guidelines, a mechanism will be put forward to allow stakeholders to voluntarily endorse them.

I am suggesting that we compete at this emerging stage and we haste not into making wrong assumptions.

We need the power to control: A lot of more investment needs to be made into the AI fireworks.

Africa can be made great.

Article by:

Derek kweku Degbedzui

Derekjr560@gmail.com

Founder, President

Ethical AI labs